Whoa, you guys are looking well. Apart from mucking about in boats, lately we’ve played around with some fresh hops.

Most commercial hop crops flower once per year, in late summer. As the flower of the female plant matures into cones they produce lupulin, a sticky yellow substance loaded with all the bittering and flavour molecules that beer drinkers crave. These compounds are pretty delicate, and rapidly emerge, transform and fade throughout the harvest window. Each varietal will also cone and produce desirable terpenes and alpha acids during specific times of the harvest.

To preserve hops and the compounds we love, growers will dry out the cone via kilning, to remove moisture and slow the metabolic activity within the cone, protecting it from oxidation. Dried cones are sometimes used in the brewing process. Cones are further processed, smashed up, slightly enriched and pelletised through a die for transport and storage. Pellets are available in the classic T-90 format, where 10% of the extraneous plant matter is removed during casting, or in the T-45 format, where 55% of the plant matter has been removed. These pellets are then vacuumed sealed under nitrogen, lasting years in good condition.

But once a year, brewers have access to fresh hops. Also known as green or wet, fresh hops have more of the very delicate aroma molecules that don’t survive drying and pelletising. Therein also lies the kicker, they oxidise and degrade extremely quickly, in a matter of hours once picked.

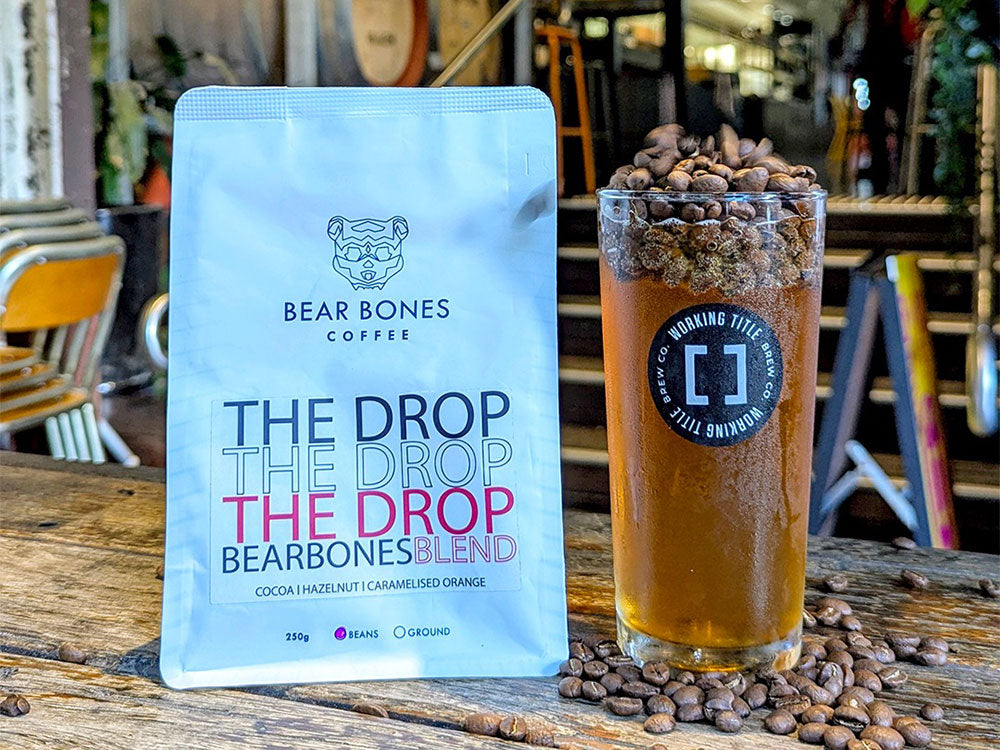

Working with @ryefield_hops in southern NSW, we embarked on platform of hop expression that explored T-90, whole cones and fresh hops. On brewday, we received T-90s of Chinook and Beedelup, a relatively obscure Australian varietal, which went in the boil, and whole cones of Beedelup, which went in the Hop Back. Three weeks later, we had some freshly harvested Columbus sent up, which went in a dry hop addition.

Of all the methods we have tried with utilising fresh hops, we’ve found dry hopping preserves the delicate aromatics the best. While this method most likely promotes oxidation, it also gives an opportunity to thoroughly purge the hops with CO2. The beer was rested on the hops for roughly a week, until we were happy with the flavours.

As well as the classic pine, resin and grapefruit citrus that you would expect from these hops, there is also a moreish honeydew melon element that is specific to fresh hops. The combo works great and in a Cold Black IPA, all the fresh hops nuances are there. But that’s a story for another time.